Horologer MING ’s Founder Ming Thein on The Past, Present and Future of an Unusual Watch Brand

Few independent brands have made as strong an impression in recent years as MING, so it’s time to sit down with its founder.

In a world where the watch industry is often anchored in heritage and tradition, Horloger MING takes a refreshingly modern approach, melding unique aesthetics with a thoughtful design philosophy. At the heart of it all is Ming Thein, photographer, designer and engineer, whose vision has propelled the brand from a bold idea to a cult favourite among collectors. In this conversation, we sit down with Ming Thein to explore the origins of the brand, the guiding principles behind its design language, and the deliberate choices that have allowed MING to stand apart in an increasingly crowded independent landscape. We talk about ambition, not in terms of volume or scale but in terms of impact, community, and horological integrity. Last, Ming Thein leaves us with just enough of a teaser to spark curiosity, hinting at what’s next for the brand and why the best might still be ahead.

Xavier Markl, MONOCHROME – Ming, thanks for taking the time. Your watches are pretty unique within the horological landscape, and this has a lot to do with your personality and background. You are a self-taught designer, watchmaker, and photographer, you are versed in engineering, you have a physics background, you are designing and photographing every single watch you make… How has this shaped what Horologer MING is today?

Ming Thein – Well, that is just half of the story. The other half is that I spent 10 years doing all of the corporate stuff, which I didn’t really enjoy. I was in accounting for a while, etc. But without all these boring things, we would not have survived. Because “what I want to make of a product” versus “this is what we can reasonably make” are two completely different things. This is a very important distinction to make.

It means that we have been around for about eight years now. This is not something that is easy to manage, specifically in the current environment. The pandemic was somehow good for small brands; a lot of people tried new things. Taking a look at how many brands keep releasing new stuff is a good indicator of what is happening in the market. We still continue to do the same 8 to 10 releases per year. I like to think this is a good indicator that we remain not just operationally capable but also creatively motivated.

There is a board in the office which has 120 different things, and these are our projects. They get refreshed when things fall off or get added, but we have a pipeline for the next 5 to 10 years. This is a consequence of us realising that we can’t just arbitrarily go “Oh, we need a new model, let’s change the dial”.

You will see with the new stuff we are going to launch in July/August, which will be our fifth-generation design language. This was designed to have a universally accommodating design from the start, in which we have about 15 or 16 main models, all of which are very different. The forward planning part is very important, and this is a consequence of my corporate background.

That is the operational part. To reach an audience is something we need to work on. I think there are brands which are trying to create stuff based on “This is what I think the market needs”. It is not the same as saying “We are going to make something unapologetic that is just for us”. We need to make things that we can defend and that are coherent and cohesive. If you ask me, and any member of the team, why this particular design is the way it is, the answer will be that it was a conscious choice for very specific reasons, not because it was in vogue when we designed it.

The other part is that I have always been a creative person, which is the photography aspect. If you look at design from a compositional standpoint, if I show you a photograph, you and everybody else see the same thing; the perspective does not change, it is static. The same thing goes for video from a certain point. Design is a much more complex three-dimensional dynamic version of that. If you see a flat view from the top, you see only one thing. But what happens when you turn it? What does the profile look like? Are there any awkward angles where the light looks wrong? This is something where I guess you need a compositional memory, where you are always trying to put elements in balance together and make sure that your hierarchy and order of reading are correct.

I have always liked watches that are visually dynamic: they change depending on how the light hits them. This is one of the reasons why we use a lot of sapphire and reflective elements, and we are very careful to use anti-reflective coatings. For instance, the dials are reflective, but the hands are not. So, you can see clearly that the hands sit above the dial because our crystals have double anti-reflective coatings. There is a very conscious thought process that goes into every element of the design. I can say this in confidence because I know that if I don’t draw that line, it does not exist. If that line does not exist, we can’t make that part. There’s nothing like “I bought this component because that’s what’s available there and that’s what fits!”

Back to the operational side of things, over those eight years, you’ve structured your activity significantly. How are you organised today?

We started with basically me doing everything and having a couple of silent partners doing a few specific things. And that worked when we were a single-project, single-product brand. The biggest operational change was made when finance and operations shifted from me to Praneeth (Editor’s note: Praneeth Raj Singh is MING’s Chief Executive Officer). He is now the corporate guy, while I am the creative guy. We figure out the high-level strategy together, and I don’t worry about the operational part; I worry about the creative part. I do the design, construction and engineering, I do the photography and all the creative bits, everything that has branding on it.

We started off with in-house designs, while the manufacturing was completely external. The early watches we had used standard Sellita movements, working with what was available and then customising them on top of that. In contrast to now, where we essentially retain the rotating components, but all the bridges and plates are completely redesigned. This is the level we are now going to, because we want to have differentiation. Part of that means that we also moved away from external partners for some things because it is faster and more flexible to work that way (internally). Additionally, the overall level of integration and control is significantly better. This led to us opening a Swiss office, where we handle assembly and all ground operational tasks. There is an ecosystem for watchmaking, somebody needs to go and find some screws or crystal, chase that supplier of metallization… That made things a lot faster and easier for us. This is something that we will probably expand in the future. Where we expand depends specifically on how we want to grow the brand.

In particular, a fairly common ambition among brands is to make movements in-house… I like the idea, but the practicality is very different. I don’t think it makes sense, for example, to create a Sellita replacement, because we’re unlikely to match the cost or reliability that would make it worthwhile. But maybe we might do something that is completely unique and in-house. And then, there is a good reason to do it.

I will end the topic with an important consequence of us moving to Switzerland – we can’t write Swiss Made on our watches anymore. I know that sounds paradoxical, given we’re doing more than before in Switzerland, but there is a clause in Swiss regulations that says that the engineering and development have to be done in Switzerland. Previously, the final construction was done by partners, even though I was responsible for the design. Now, I am doing everything apart from adding machining tolerances because all of those are machine-specific, so without knowing what machine our partners will be using, it is better for them to do so. So, according to Swiss regulations, the construction is now done in Kuala Lumpur. I can sit at my desk in La Chaux-de-Fonds or at my desk in KL, and I do the same work. But if I do it in La Chaux-de-Fonds, I can say that our watches are Swiss-made.

It is paradoxical indeed. But to be fair, I think you have reached a point where your watches are beyond having the Swiss-made label or not… But let’s get back to design. Looking at your watches, something that comes to mind is the materials and the technicality, things people might not have expected from such a small and young brand.

I think it goes back to making things that we want. My background as someone who appreciates beautiful objects and enjoys tactile interaction with them led me to ask what we could do to create objects that have a certain tactile impact, as opposed to a certain visual impact.

The lightweight is a good example of that because the whole idea of making an ultralight watch is a complex philosophical thing. I could inject you with a timing chip, but is it a watch? It is not. I could make something out of plastic or carbon or some exotic light materials; it might be very light, but it lacks certain tactile qualities that you would expect from an expensive watch. It would not feel light; it would feel cheap. The rules that we set for our watches are: 1) it has to be metal i.e. you have to feel the properties of metal, it is cold when you pick it up; 2) it has to look like a watch too, so if you show it to non-watch people and ask them what it is, they would say “well, that’s a watch”; 3) It needs to be practical too. To keep it reasonably priced, we did not develop an exotic movement for it. If you think about it, these are pretty tight constraints because if you could develop a movement from scratch and make it any size you wanted, would you make it 5mm in diameter and in plastic? This is too easy. We chose the difficult way; the metal we use feels like metal, it is 38mm in size, and it uses a modified ETA movement. We start with the idea of a certain utility and certain look, and then go and find the materials.

Another aspect is that we continually scout for new technologies and materials to work with. For instance, the fused borosilicate dials made with Femtoprint that we used in the 20.01 series 3 came from a meeting that Magnus took at EPHJ a couple of years back (Editor’s note: EPHJ is the main watch industry fair dedicated to suppliers and subcontractors). He asked me, “Can you do anything with this?” I think it over, and then later on, I say “This is what I want to do conceptually, and this is the technology that we are going to use”. The team is currently at EPHJ doing just that. I have given them a shopping list of things that I want to find from a technological point of view, and they will come back saying this is what we have found, and maybe this is interesting. It gets better every year. They know what I am looking for. We have had a lot of new technologies emerge from this. We were the first to do the three-dimensional laser mosaic in the 20.01 series and we had the fused borosilicate dials. The watch we’ll be releasing in a couple of weeks will use a new technology for micro-machining titanium, and we have also developed the tantalum bracelet. The tantalum case of the Project 21 has a very interesting finishing – it is a monobloc with a mirror polish, fine satin and dark beadblast, and we did that with Josh Shapiro. These things keep growing and growing and growing… I have got several things on my desk that I cannot show you now that are truly interesting.

It’s not just about the materials, but figuring out what you can do with them that adds to the overall experience. I don’t want to make a watch, for instance, out of stone because nobody has done it. To me, it does not make sense. But if we make a part of the watch out of stone that adds something to the overall feeling or creates a unique aesthetic, that is justifiable. I think this is what we should be doing. There will be a lot more of that coming.

You have been 8 years now on that MING journey, what is your ambition, and what are your challenges today?

Let’s start with the challenges because this is not an easy market for everybody. Last year was tough; this year is slightly better. It is a challenging market for everybody at the moment.

Our biggest challenge is “how do we balance development and pushing the envelope, allowing everybody to catch up and also trying to figure out how to keep it financially viable?” You can blow a lot of money on R&D and come up with a product that nobody understands because it is too different. We want to avoid doing that. We want to come up with products that speak for themselves. Products that are very different from anything that has come before, but do not require a manual to use or understand. We are trying to avoid doing things for the sake of doing them, but at the same time, we are trying to do things that are increasingly difficult. Some of this can be overcome by intelligent design, and it is entirely up to me to solve. This is one of the biggest challenges because all of the easy stuff has been done.

From the early days, we’ve had a system for special projects, where I go and see half a dozen collectors and say, “This is what we are going to do, it may or may not work, but you are going to get something special. Are you willing to buy it?” Those loyal supporters are the ones who fund the development. That trickles down to the mainstream. I think there is always going to be a group of people who are on the leading edge of perceiving something as special. Fortunately, this is how we will continue to find our balance.

I don’t think growth for the sake of growth makes sense. I want everybody to have the same quality of experience, and when you increase the number of transactions, it does mean that the level of personal interaction required diminishes. We are probably going to maintain the same number of watches per year or eventually reduce it. We’ll figure out what it means in terms of product offering.

We have started doing retail this year – we realised that we can’t be everywhere, and there are people who want to see our watches, but we can’t easily get to them. There will be more retail locations, with independent watch retailers like Collective Horology, for example. They can reach an audience that we can’t, allowing us to expand our coverage and show more people our watches.

Importantly, we still have to make products that we like. It is very easy to say “integrated bracelet watches” are popular, so let’s just make one of those. A watch is a completely unnecessary product. To be blunt, if you don’t feel good about buying a watch, and about wearing a watch, you should not do it. This is fundamental.

A more philosophical question. What has been the process and journey of going from a passion project to a brand with a community and identity larger than the people who started it?

This is a tricky one to answer. There are things I realised earlier on when I was in photography. If you have five billable shooting days, this is a good month. The rest of the month, you do location scouting, commercials, pitches, your accounting, your taxes… To do 5% of the enjoyable work, you have to do the other 95% too. I think if I did not know that going in, I would be very disillusioned. It is rare for me to spend all my days designing. Most of the time is dedicated to problem-solving, meeting with suppliers, and figuring out the strategy.

When we started having employees, we transitioned from things being 100% about what I want to do to needing to be responsible for the company, the brand, the people we employ, our customers, and everything else. The perception changes quite a bit. I think I need to be more objective now. I know there are things that we do that won’t please everybody. Between when we started and now, the cost of the same Sellita base movement has doubled, and there is no way we can maintain the original price for many reasons. Tough. But you won’t have a brand if you can’t run it sustainably. At the same time, we have customers who have been with us since day one, and we are always asking ourselves how we can keep that loyalty. If we were to buy something from a brand, what would we want to see that keeps us engaged and interested?

These are questions that you don’t typically ask as a young brand. You ask about the product and the experience that you want to have; you don’t ask How do I stay loyal? What is going to keep me coming back? How do I differentiate myself? How do I differentiate the next product from all the previous ones without making the previous product look any less, without alienating all of the things that people liked? It is hard, and it gets harder.

What can we expect from MING in the coming months?

Well, I’ll give you a descriptive teaser of, let’s say, the next 18 months…

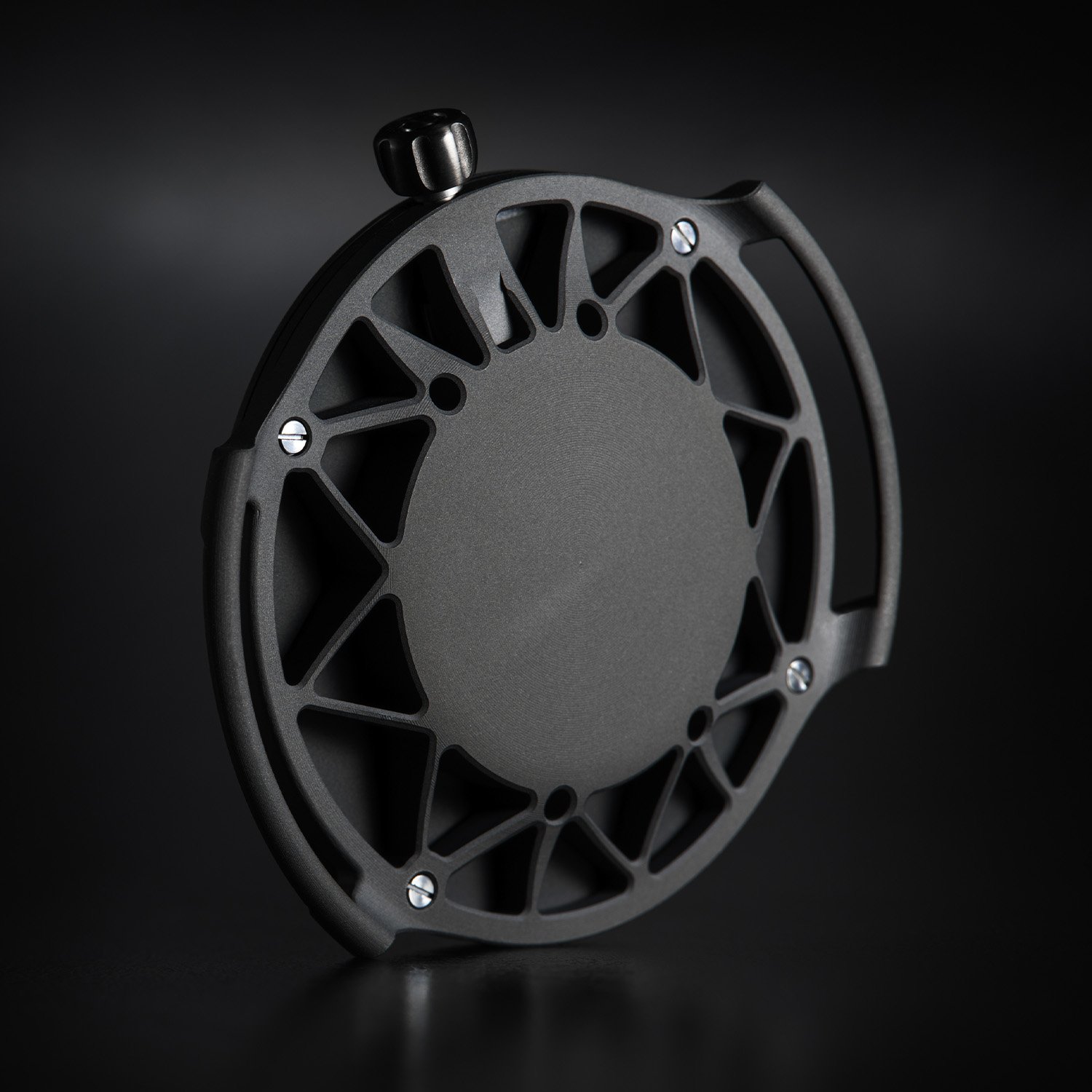

Our fifth-generation design language debuts in August, in the shape of a mono-pusher chronograph at a price point we have never done before. For a mono-pusher chronograph, it will be a fairly low price point. It is a completely new case construction. When you look at it, the initial impression is extremely crisp, and then if you look at it more closely, you go, “How on Earth does this go together?” There are adjacent surfaces that are finished in a way that should not be possible. That will be interesting.

Then we will have a new micro-machining technique with a one-piece titanium dial. This one has a lot of depth; it looks like it is made of different pieces, but it is not.

We have a new artist collaboration coming. We have an integrated bracelet watch. We have been working on it for 4 years. It is very difficult to do something that is different in this category and that still functions correctly. This has been challenging to integrate into our design language. To continue our design distinctiveness in a different format has been challenging. It will have micro-adjustment, and everything you expect. I have spent time with the most popular integrated watches, trying to understand what’s good and what’s not about those designs. The conclusion I came to is that unless the balance is perfect and unless the adjustment is perfect, integrated bracelet watches are not comfortable. The one thing we tried to get right is the flow of the bracelet, the balance of the watch versus its bracelet and the adjustability. Without those things, it does not make sense to do an integrated design… It took a lot longer than expected.

The last thing is that we are working with a high-end independent brand, which will provide a movement around which we will make a watch with a material that has never been used in watchmaking. But I can’t tell you more right now…

For more information, please visit www.ming.watch.